Some have called for Morehouse College students and faculty to protest President Joe Biden’s planned commencement address next month at the school, criticizing his administration’s support of Israel in its ongoing war against Hamas.

For now, it’s unclear if anyone will heed the call to protest. What’s clear is Morehouse and Atlanta’s other historically Black colleges and universities have a long tradition of participating in social justice movements and protests on an array of issues.

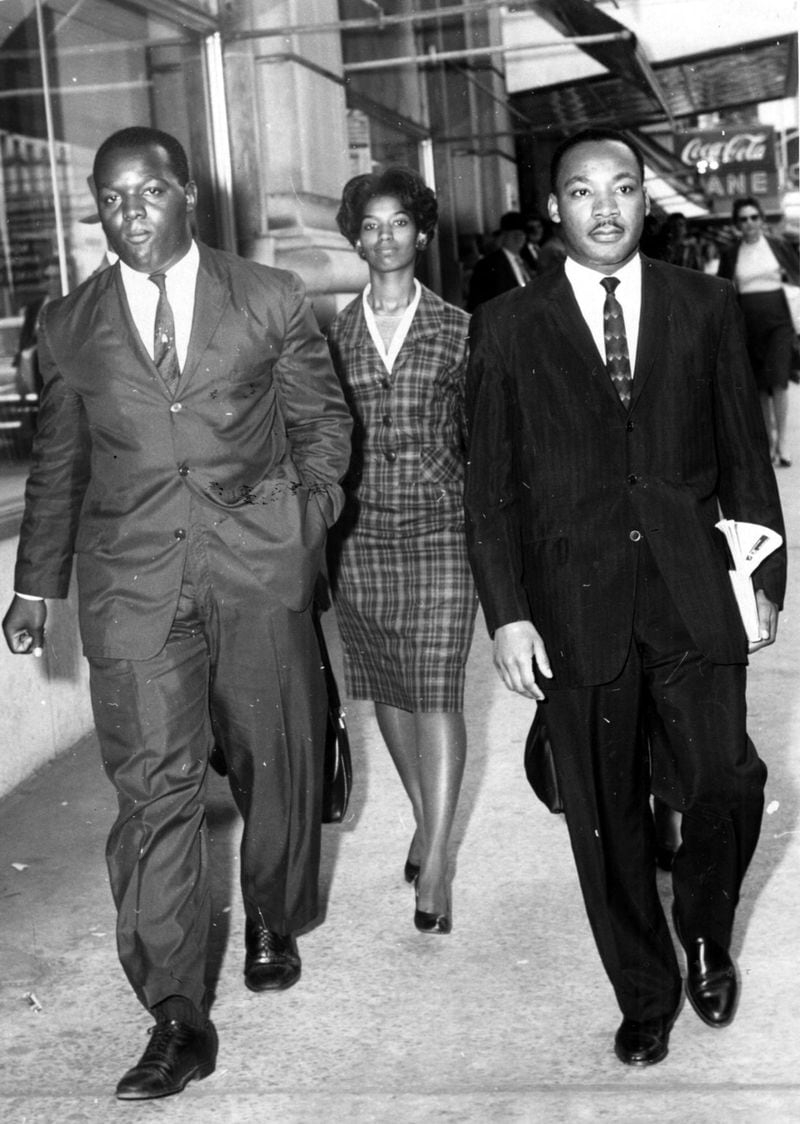

The recent history dates back to 1960, when thousands of students and adults marched on the Georgia Capitol and downtown businesses to fight segregation.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was invited to join the Atlanta sit-in and was arrested alongside students under a 1960 law that made refusing to leave private property a misdemeanor offense. While many arrested were dismissed at their first court appearance, King was sentenced to six months of hard labor. He was released shortly after presidential candidate John F. Kennedy contacted the King family. The call was credited with swinging many Black voters to Kennedy’s campaign, helping him with the presidency.

The protests and an economic boycott cost downtown businesses millions of dollars and eventually led to the desegregation of many Atlanta stores and restaurants. In 2010, the city of Atlanta named a street in honor of the students.

“They took on such a Herculean task,” Councilman Michael Julian Bond said of the students.

Credit: Unknown

Credit: Unknown

In the mid-1980s, students from Morehouse helped lead protests against apartheid in South Africa. Some of the protests were directed toward Coca-Cola, the Atlanta-based beverage giant, to demand full divestment of its holdings in that country.

Local HBCU students in recent years have been involved in Black Lives Matter demonstrations to protest the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and other cases. Not all of the protests have been well-received. In 2016, former U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young, a civil rights icon, called the Black Lives Matter protesters who were involved in an effort to run onto the Downtown Connector “unlovable little brats.” Young, a former Atlanta mayor, apologized for the comment shortly thereafter.

In 2020, many of Atlanta’s HBCU students were active in protests after the George Floyd killing.

A year later, several dozen students protested for improved student housing and that congressional elected officials from Georgia provide more funding for the schools and student loan debt relief. Some began the protest outside Rush Memorial Congregational Church at the Atlanta University Center, where HBCU students organized demonstrations in 1960.

Some protests have become memorable for who was involved in the demonstrations. In 1969, Samuel L. Jackson was expelled from Morehouse for locking board members in a building for about two days in protest of the school’s curriculum and governance.

“The Morehouse College administration was rooted in some old-school things that the majority of us students didn’t believe ... I didn’t want to be just another Negro in the, you know, advancement of America card. We had no connection to the people that we lived around. I was skeptical of that. We didn’t even have a Black studies class. There was no student involvement on the board. Those were the things we had to change,” Jackson, who became a global movie star, told the Hollywood Reporter in 2018.