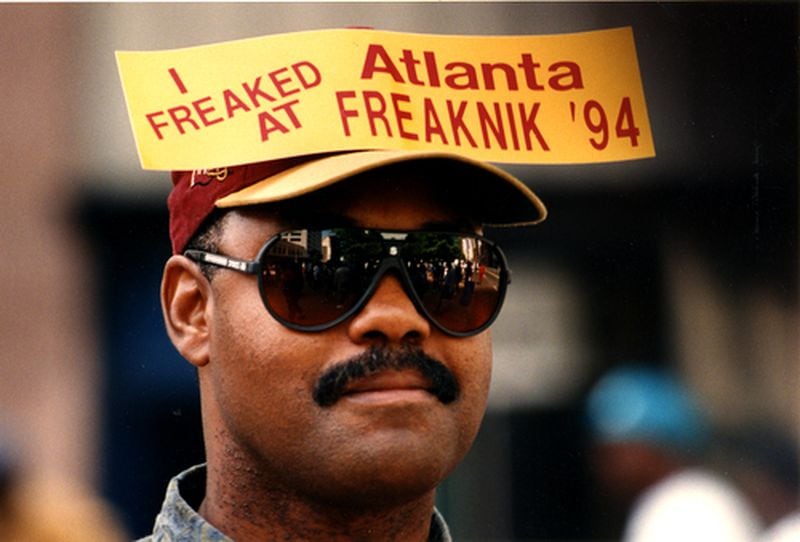

Freaknik started as a picnic but it eventually morphed into a raucous gathering of thousands of young people, a history highlighted in the new Hulu documentary “Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told.”

But there’s another part of the story that hasn’t been widely told — the behind-the-scenes tension between Black political leaders in the city around the event, and the role a storied civil rights organization played in trying to calm Freaknik down.

The first Freaknik was held in 1983 for Atlanta HBCU students staying in the city for spring break. The inspiration for the name came from Chic’s 1970s hit song “Le Freak,” the founders said in the Hulu documentary.

Eventually, “freak” came to mean something different. As word of the gathering grew it evolved into a party that took over the city and, by the mid-1990s, attracted hundreds of thousands of young people from around the country.

In 1994, a city-sanctioned committee called the Atlanta Student Forum was created. Its goal was to organize Freaknik events and put structure around the gathering, which the committee tried to rebrand as “Atlanta Black College Spring Break,” according to published reports in the archives of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

But the forum, which included representatives of the city, police, business leaders and Atlanta University Center student government — including Stacey Abrams, who at the time was student body president of Spelman College — scrambled to get events organized that year. Ultimately more established party promoters ran the events and an estimated 200,000 people came, bringing Atlanta to a standstill.

In 1995, Mayor Bill Campbell changed his stance on Freaknik, vowing to crack down on the party. This provoked outrage among some student and city leaders.

However, the students had an unlikely ally: the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the civil rights organization co-founded by Martin Luther King, Jr.

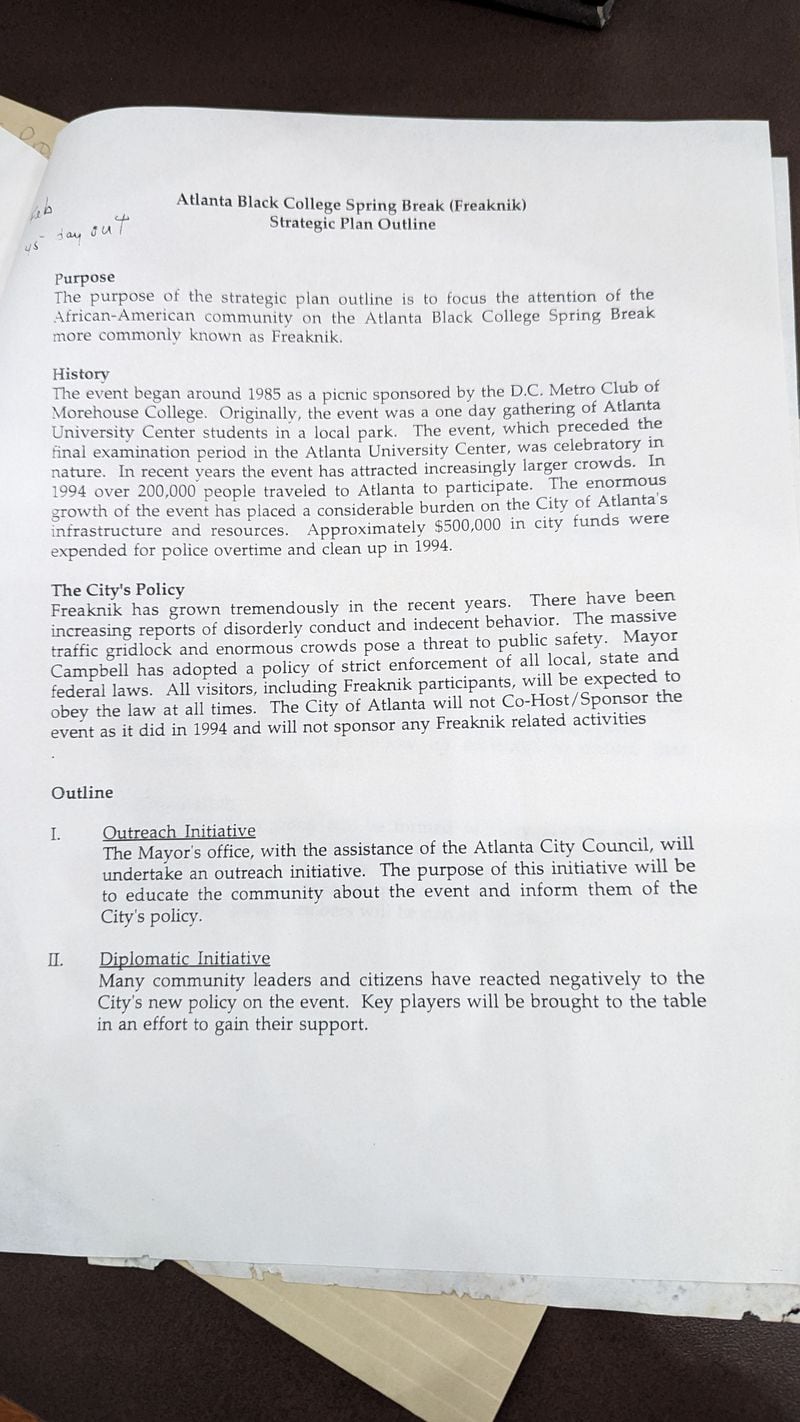

In February 1995, about 45 days before Freaknik, the SCLC put together a strategic plan. It aimed “to focus the attention of the African American community on the Atlanta Black College Spring Break more commonly known as Freaknik,” according to documents in the SCLC’s archives, which are housed in the Joseph Echols and Evelyn Gibson Lowery Collection at the AUC’s Robert W. Woodruff Library.

Credit: Mirtha Donastorg

Credit: Mirtha Donastorg

The plan proposed several initiatives. There would be outreach by the mayor’s office, diplomatic efforts to bring to the table people who were opposed to the city’s handling of the event, a traffic plan to prevent gridlock, and guidance that publicity should be handled by the mayor’s press secretary.

The February plan also outlined a four-step action plan involving Campbell, the city council, ministers and community leaders. But the plan does not seem to have been implemented.

In late March, weeks before Freaknik was set to start, the SCLC created an addendum to their February plan. They identified facilities to host events in four quadrants of the city, parking locations to ease traffic congestion and a proposal to create a central information center.

The document also outlined a need for portable toilets and a strategy to work with Black radio stations to disseminate traffic instructions.

“Let us remember the catalyst for this plan is to create an atmosphere of accommodation and reduce the climate for defiance and truancy,” the organizers wrote.

But if those efforts weren’t successful, they had a contingency plan to:

1. Create a church network and information center that could provide temporary housing, information, counseling and motivational forums

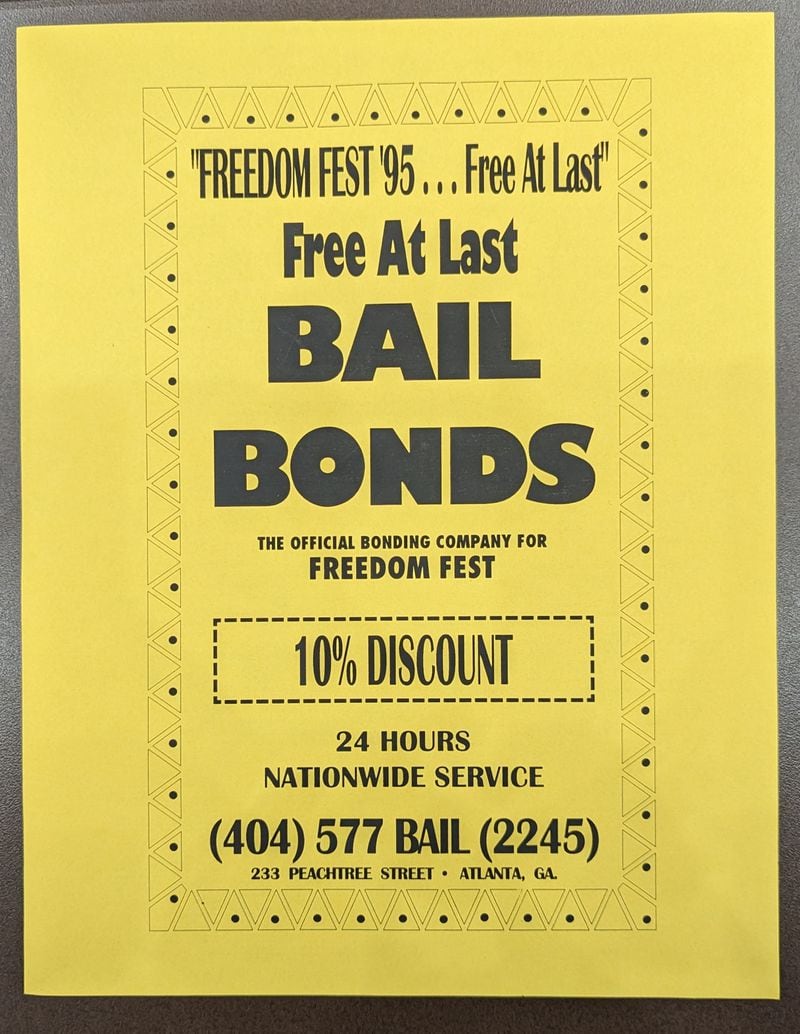

2. Organize legal teams and bail bond resources that could communicate with parents outside of the city or the state

3. Identify medical resources

4. Facilitate housing accommodations

The SCLC was also a part of a coalition that tried to rebrand the event to “Freedom Fest.” The retitling was posited as more than a change in name, but “a change in spirit, change in attitude and change in direction,” according to a Freedom Fest brochure in the Woodruff archives.

Campbell and the SCLC did not respond to requests for comment on the city’s 1995 Freaknik efforts.

Ultimately, Freedom Fest didn’t gain widespread support and that year’s Freaknik didn’t look much different than its predecessors. The SCLC put together a goodie bag which included a brochure with survival tips, a flyer for a bail bondsman and a Georgia voter registration form, among other things.

Credit: Mirtha Donastorg

Credit: Mirtha Donastorg

In 1995, Atlanta took a harsh approach, just as Campbell had promised. Barricades were set up around the city, snarling traffic and, in one case, delaying a couple headed to a hospital because of a miscarriage, according to an AJC report at the time.

Some of the partygoers caused mayhem. Rich’s department store in southwest Atlanta was looted, and a candlelight vigil was held for women who were harassed during the festivities after Freaknik concluded.

Credit: TNS

Credit: TNS

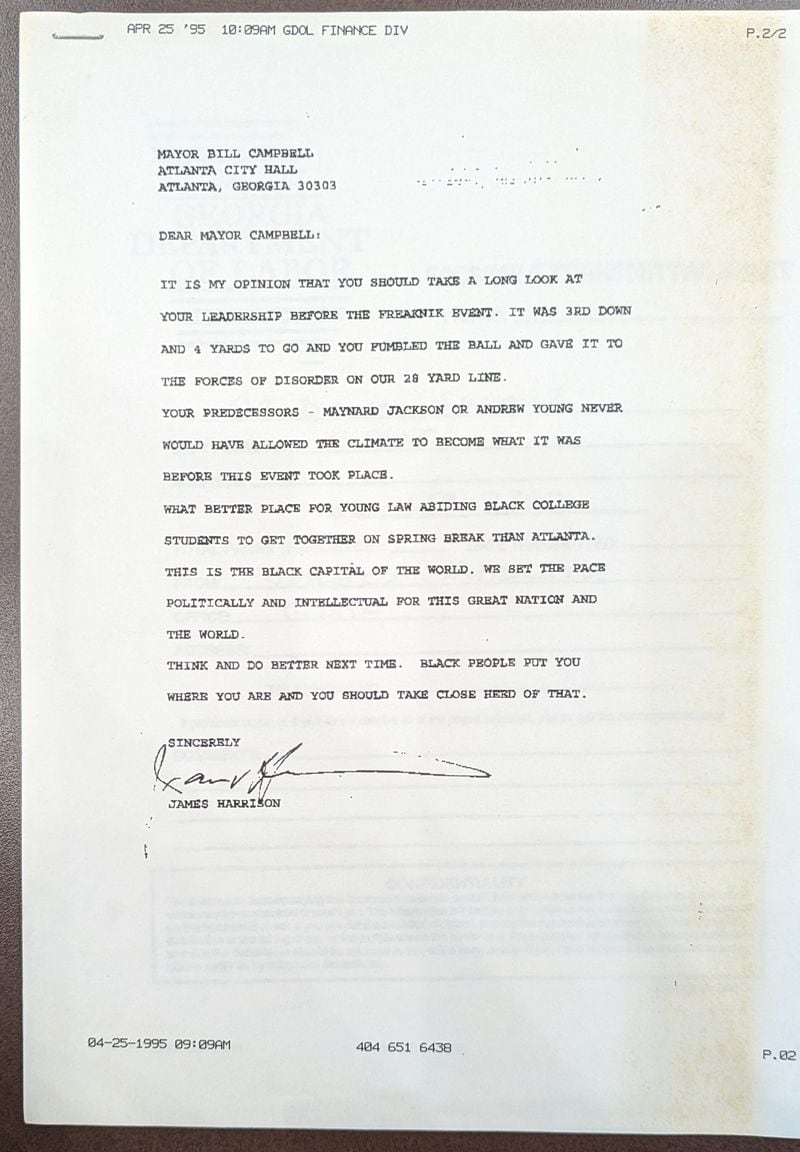

Freaknik 1995 also left some Black residents feeling disillusioned and even caused a political headache for Campbell that led to a short-lived recall effort.

A man from the Georgia Department of Labor wrote a letter to Campbell just days after Freaknik ended, excoriating the mayor’s handling of the event.

“It was 3rd down and 4 yards to go and you fumbled the ball and gave it to the forces of disorder on our 28 yard line. Your predecessors — Maynard Jackson or Andrew Young never would have allowed the climate to become what it was before this event took place,” James Harrison wrote.

“Think and do better next time,” Harrison typed in conclusion. “Black people put you where you are and you should take close heed of that.”

Credit: Mirtha Donastorg

Credit: Mirtha Donastorg

In May 1995, a local resident filed recall papers against the mayor “because, he said, Campbell ‘violated the human rights’ of college students who traveled to Atlanta in April for Freaknik by calling out an army of police to maintain order,” according to a 1995 AJC report. Civil rights activist Rev. Hosea Williams threatened to support a recall if Campbell didn’t put together a committee on Freaknik/Freedom Fest.

Campbell ended up remaining in office, but Freaknik was an issue that followed him.

“All the other problems have a reasonable solution,” Campbell said in 1996, according to the Washington Post. “This issue does not.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Report for America are partnering to add more journalists to cover topics important to our community. Please help us fund this important work at ajc.com/give

About the Author