The latest last-ditch measure to place short-term restrictions on mining near the Okefenokee Swamp was originally born a year ago as a bill to restrict Chinese nationals from buying vast tracts of Georgia agriculture near military bases.

Backed by Republican state Sen. Brandon Beach, a close ally of Lt. Gov. Burt Jones, it easily passed the Senate on a party-line vote amid pleas by supporters to “prevent Communist China from buying farmland in Georgia.”

But the final days of the legislative session are nothing if not full of intrigue. And Beach’s bill was transformed — or, as Beach would put it, hijacked — by House Speaker Jon Burns and his allies to become something entirely different.

The measure, Senate Bill 132, would not prevent state environmental authorities from issuing permits to Twin Pines Minerals for the 582-acre mine at the center of national conservation efforts.

But it would pause permitting of new mines that use the same sort of “dragline” technique that the Alabama company plans to employ to unearth part of the ancient dunes that run along the east side of the swamp, mainly for a compound used in toothpaste and paint.

Credit: TNS

Credit: TNS

Some of the mine’s opponents have begrudgingly embraced the bill as a step to limit future excavations on the fringes of the Okefenokee Swamp that conservationists say would imperil one of Georgia’s natural treasures.

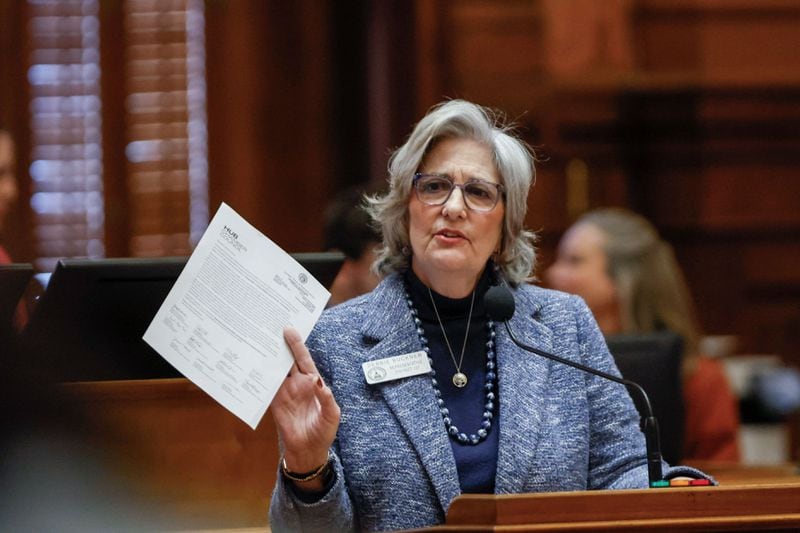

State Rep. Debbie Buckner, one of the chamber’s few rural Democrats, told her colleagues Tuesday they’re “not getting the best” with the reconfigured measure. “But we’re getting something good that will help us take care of the swamp.” Later, she reconciled her vote in an interview: “It’s better than nothing.”

It cleared the House Tuesday by an overwhelming 167-4 margin, with some conservation groups praising it as a solid step. Vote totals can be misleading, though, and even measures with widespread support can face long odds of reaching Gov. Brian Kemp’s desk. The bill has also been blasted by some environmental groups, who say it is short-sighted and does little to protect the swamp.

With just one day in the legislative session left, supporters fear the Georgia Senate won’t take up the issue. And a key lawmaker is resolved to blocking it on Thursday when lawmakers convene for the last throes of the 40-day session.

How did we get here?

Nowadays, signs reading “Save the Swamp” and “Protect the Okefenokee” are common on leafy yards across metro Atlanta. But environmentalists spent nearly five years rallying the public, and public officials, to move against the mine.

Their campaign yielded the Okefenokee Protection Act, a bipartisan measure meant to prevent mining expansion on the swamp’s eastern flank. The bill received a hearing in 2023 but no further debate in committee this session. And it has still never gotten a vote. That still baffles legislative veterans.

“It’s absurd that a bill that has over 90 signatures from House members can’t even get a hearing in a committee,” said state Rep. Stacey Evans, an Atlanta Democrat who ran for governor in 2018.

Credit: Arvin Temkar/AJC

Credit: Arvin Temkar/AJC

There are plenty of theories about what prompted the lack of traction of stronger protections. Some point to Twin Pines’ history of political donations, its effective lobbyist corps, or the promises of economic development to a downtrodden southeast Georgia community.

The company, meanwhile, has dismissed critiques of its extraction process. Steve Ingle, the mining company’s president, notes that state environmental authorities have mostly agreed with the company’s contention that the mine won’t harm the swamp.

That doesn’t mean the process it uses to dig up titanium sands is free of concern. Environmental advocacies say it’ll pose irreparable risks to the swamp and surrounding wildlife, and some scientists have raised sharp issues.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

The project took a major step forward last month when the Environmental Protection Division released draft permits for the development. That triggered a comment period that closes on April 9. After that, state officials can issue a permit at any moment.

The deadline, combined with the looming end of the legislative session, led to even fiercer pressure. Thousands of emails and letters flooded lawmakers. Visitors to Okefenokee sent emotional messages begging officials to “save the swamp.”

The pleas for action quickly reverberated through Burns’ third-floor Capitol suite. A timber farmer, Burns has long tried to balance environmental protection with property rights. The EPD’s impending decision added more urgency.

Burns decided on a compromise plan. He wouldn’t go as far as banning future mining across all of Trail Ridge. But he would back legislation that prevents the state from considering new permits for “dragline” mining for three years.

The compromise comes with its own perils. Chief among the concerns of conservationists is that the moratorium wouldn’t extend to other mining techniques, such as those used by the materials giant Chemours, which has nearby projects in southeast Georgia and North Florida.

Some environmentalists also worry there is wiggle room in the bill that could still allow Twin Pines to expand beyond their planned 582-acre footprint while the moratorium is in place. The company owns 8,000 acres near the swamp, and other major landowners in the area have expressed interest in allowing mining on their land, too.

“Arguably, the passage of this bill would put the Okefenokee at greater risk than ever before,” said Josh Marks, an environmental attorney who has fought mining near the swamp for decades.

A ‘queasy feeling’

The news of the bill’s approval in the House was met largely with silence in the Senate, which was rushing through dozens of measures of its own before the final gavel bangs on Thursday.

Jones and many of his allies have said little publicly about measures to limit mining on the edge of the Okefenokee. As president of the Senate, however, he gets final say over which measures reach a vote and which are rendered moot until next year.

That’s where Beach comes in. The Alpharetta Republican is one of the most outspoken Donald Trump supporters in the Legislature and a likely candidate for higher office in 2026. He’s also on the outs with key leaders in his own party.

He was demoted by Jones’ predecessor for pressing baseless allegations about the 2020 election. His support for Kemp’s challenger in 2022 made him so reviled by the governor that Beach’s friends joke he couldn’t even pass gas in the chamber.

But Jones’ 2022 victory as lieutenant governor ushered in a new inner circle in the Senate. Jones helped ensure Beach a spot as the chairman of the influential Economic Development and Tourism Committee and considers him one of his most loyal allies.

For two years, Beach fought for legislation to “defend Georgia’s farmers from Communist China’s farmland acquisitions.” A similar measure already passed both chambers and is awaiting Kemp’s signature, but Beach prefers his version. He said he’s opposing the Okefenokee bill for that reason — and is encouraging Jones to do the same.

Much can happen in the final day of the legislative session. But much also gets left on the cutting room floor. Buckner isn’t terribly optimistic.

“I just don’t know what’s going to happen in the Senate,” said Buckner, who hails from the rural town of Junction City. “I have a queasy feeling about it.”

Credit: Miguel Martinez/AJC

Credit: Miguel Martinez/AJC