“Come on, Dad, let’s go,” I pleaded.

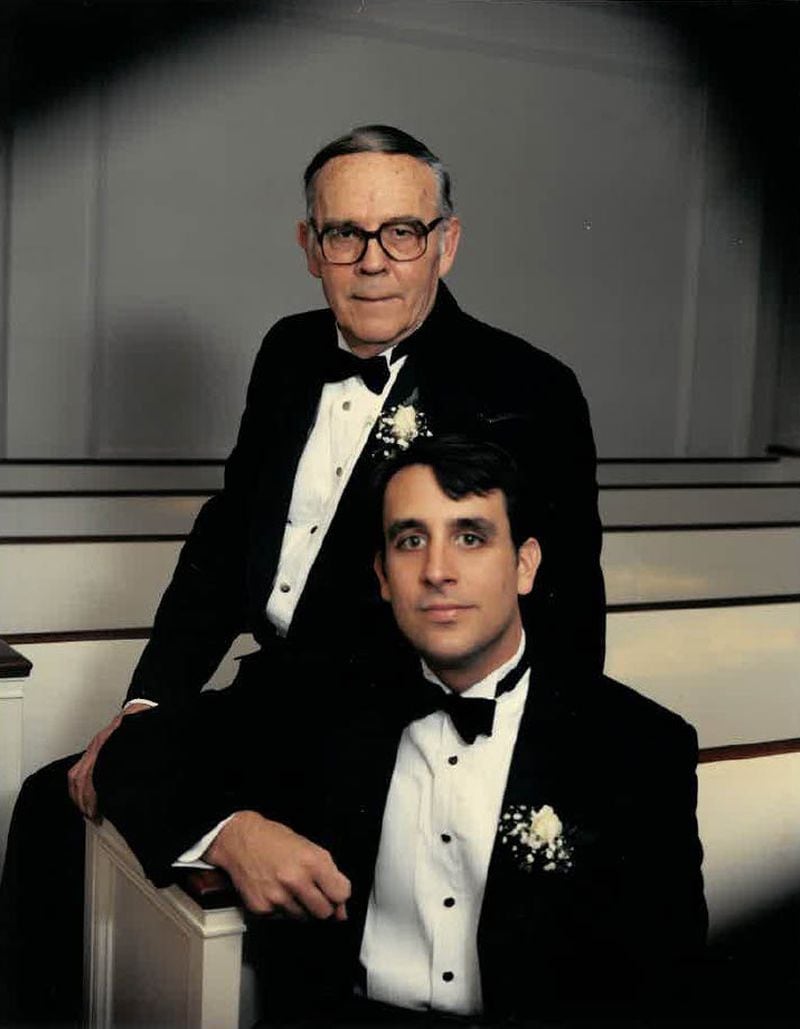

But my father, Jim Rankin, then a city editor for The Atlanta Constitution, kept standing there. We’d just waited in a long line outside the Will Call window and finally got the tickets to the night’s game. It was time to go inside and get to our seats. Now.

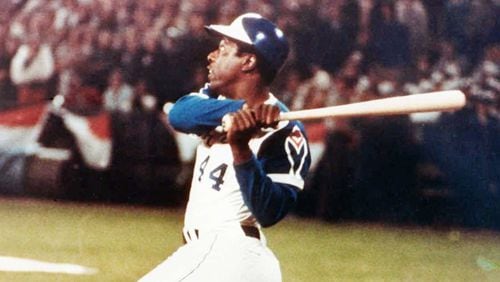

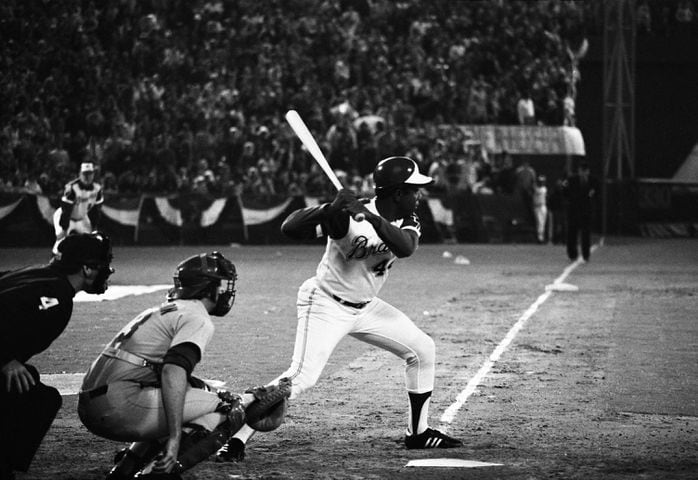

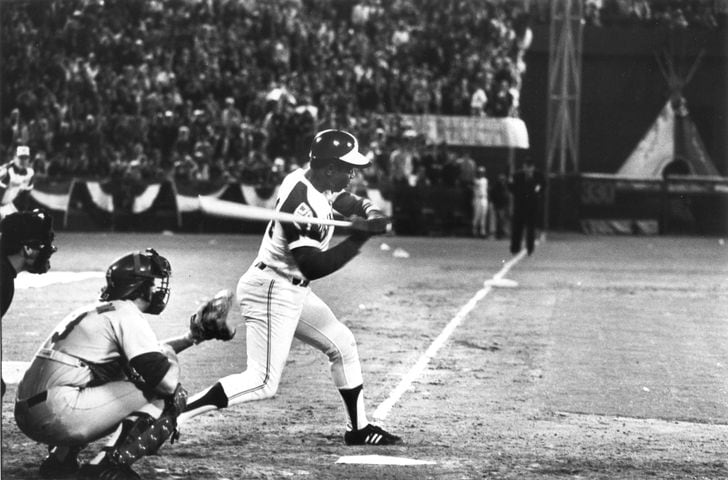

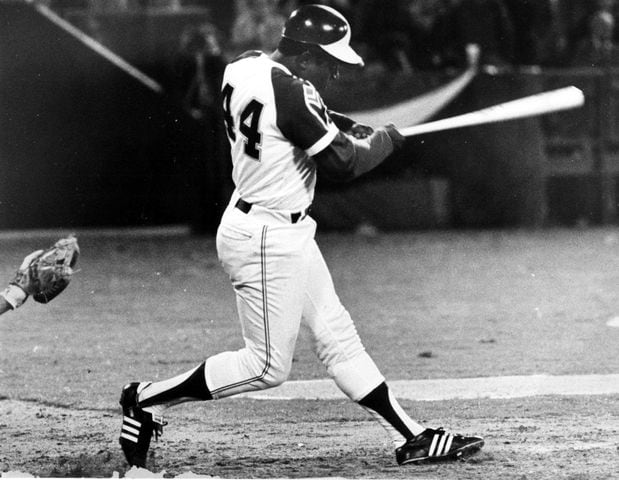

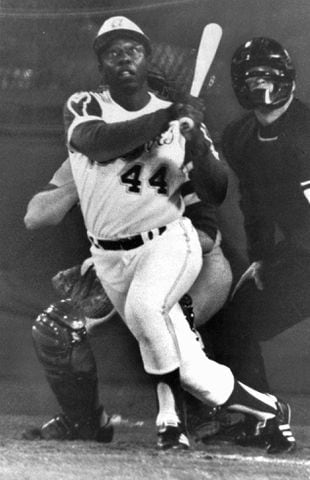

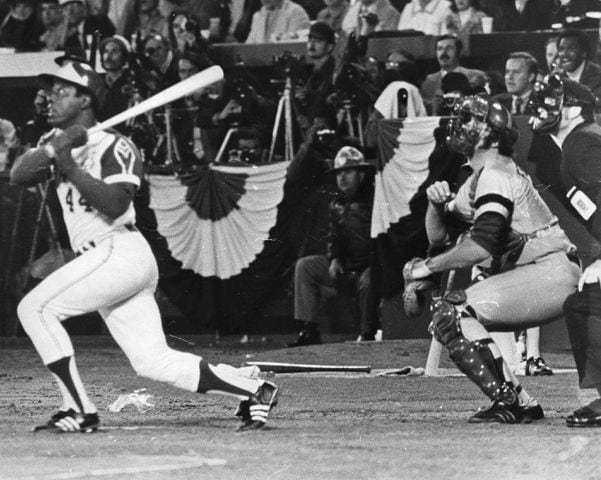

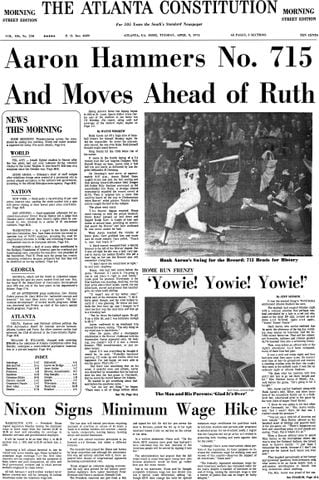

Officially, it was my Atlanta Braves against the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974. But really this was all about my childhood idol, Henry Aaron. That’s because he was sitting on 714 homers, one shy of breaking Babe Ruth’s record, the record so many had said would never be broken.

“Just wait a minute, Billy,” he said. “Be patient.”

Be patient, he said. Right.

A few moments later, a young man ran out of the stadium and handed Dad a brown paper bag. He had a big grin on his face and nodded to Dad. I had no clue what was going on.

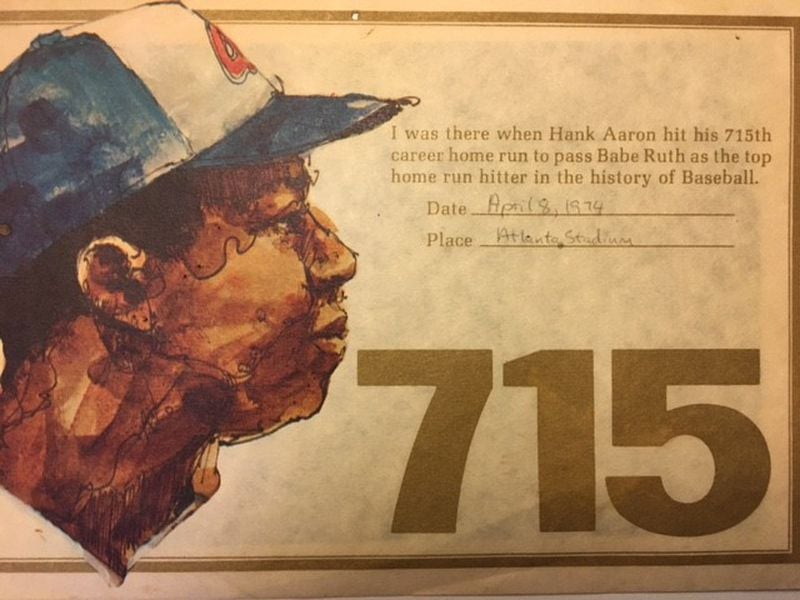

After the man (one of our sportswriters, it turned out) ran back inside Atlanta Stadium, Dad handed me the bag. Inside was a baseball with an autograph in blue ink: “Hank Aaron.”

I hugged my dad and thanked him over and over again. I mean, there was no bigger fan of the Hammer than me on the planet Earth. Not one. Impossible. When the Braves moved to Atlanta in 1966, I was 7 years old and quickly became a huge fan.

Credit: Photo provided

Credit: Photo provided

Pretty much from Day 1, Aaron was a supernova, exerting a kind of gravitational pull that seemed to draw nearly everything in my baseball universe into his orbit. He quickly became – and remains – my favorite player of all time. Over the years, I went to many, many home games and never missed them on TV, most always watching them with Dad.

At the stadium, I liked to sit above right field, where Aaron roamed. He’d run out to his position, elbows typically tucked to his sides. And it wasn’t like he was jogging or running. He was gliding. He seemed to do just about everything with so much grace and ease.

At the plate, his powerful, lightning quick wrists helped Aaron hit hundreds (and hundreds) of home runs. And, amazingly, he also hit for average. As former Braves first baseman Joe Adcock famously said, “Trying to sneak a fastball past Hank Aaron is like trying to sneak the sunrise past a rooster.”

Dad took the paper bag from me and put it in his jacket pocket. (That prized possession would be displayed on my bookshelf at home for years to come.)

“Let’s go,” he said. “It’s time.”

When we got to our seats I was elated. We were about 25 rows up between home plate and first base. The atmosphere was electric. The stadium was packed. And the threat of a rainstorm only heightened my anxiety.

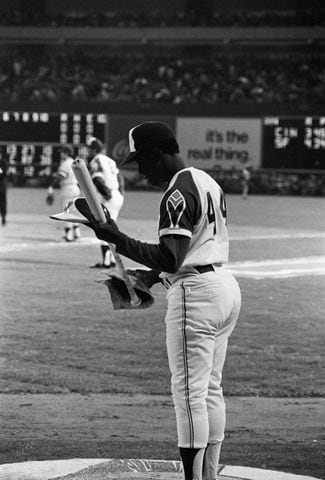

;This was the fourth game of the season. The Braves had opened it with three away games in Cincinnati. In Game 1, Aaron tied the Babe with homer No. 714 off pitcher Jack Billingham. It was his first swing of the season.

Wanting the Hammer to break the record at home, the Braves sat him for Game 2 of the series. But then Commissioner Bowie Kuhn made himself a pariah to Braves fans when he warned the team there would be serious consequences if Aaron didn’t play in Game 3. So he played, and it was the only time I was happy to see him go hitless.

So now Dad and I were at the game. I was as excited as could be.

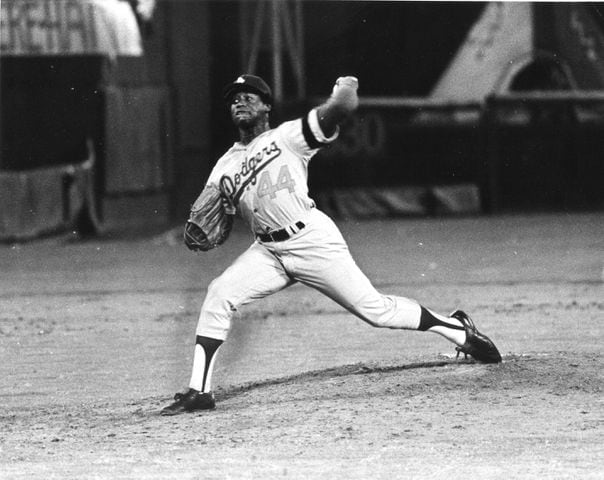

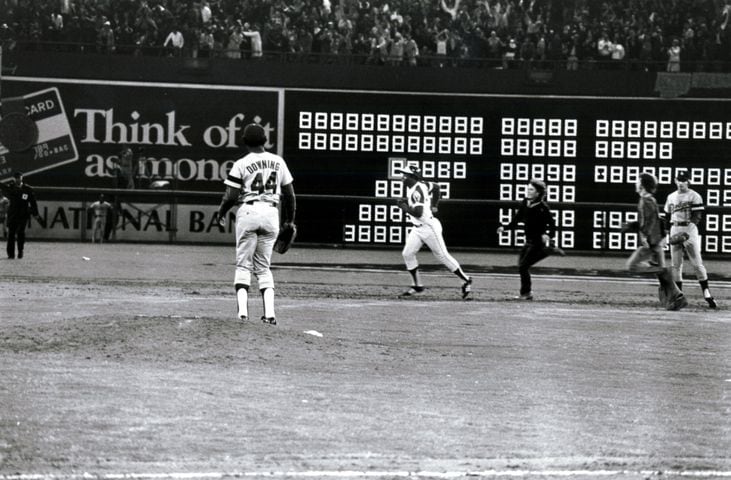

When Aaron, batting cleanup, came to bat in the bottom of the second inning, everyone stood. And when the Dodgers’ pitcher, Al Downing, walked Aaron on five pitches, I booed with the rest of the sellout crowd and screamed, “Throw him a strike!”

In the bottom of the fourth, Aaron returned to the plate with a man on first. When Downing’s first pitch was in the dirt, it made me wonder: Will my hero get a pitch to hit? Was this not going to be the night? And, of course, I booed along with everyone else. With gusto.

But that didn’t last long.

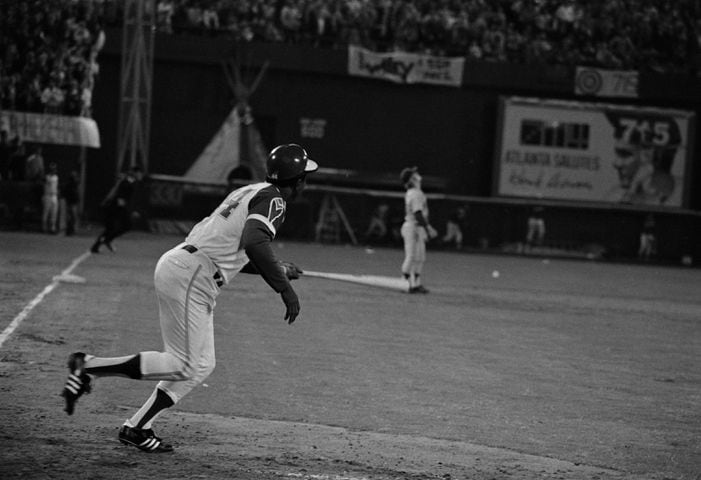

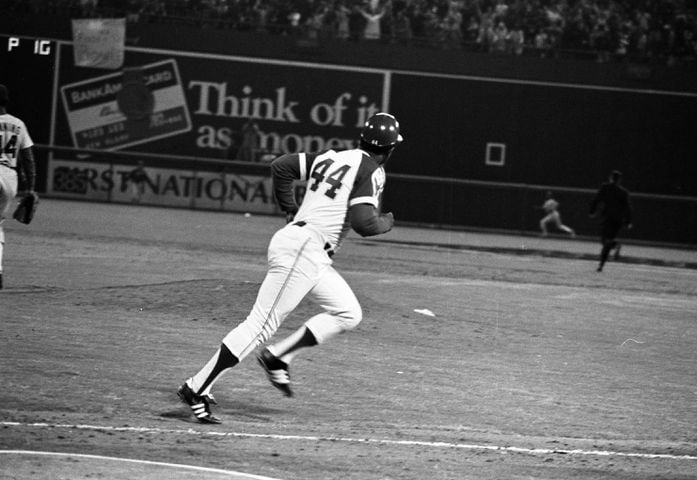

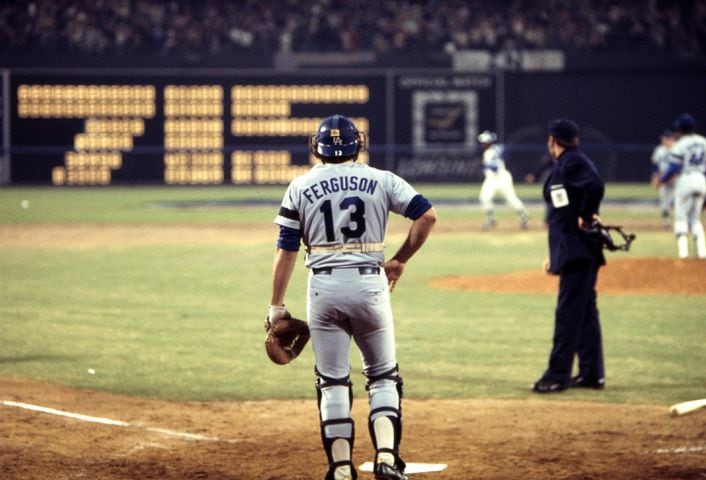

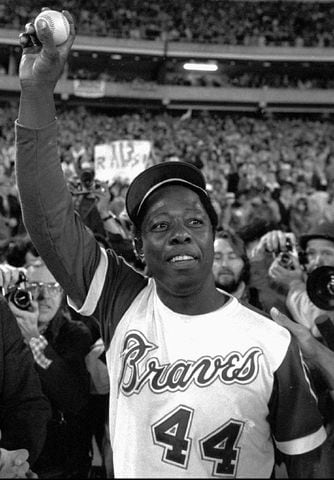

Downing’s next offering was right down Peachtree, and Aaron crushed it. A beautiful, wonderful, glorious no doubter over the left field fence. Not only that, it was Aaron’s first swing of the game.

Credit: Photo courtesy Bill Rankin

Credit: Photo courtesy Bill Rankin

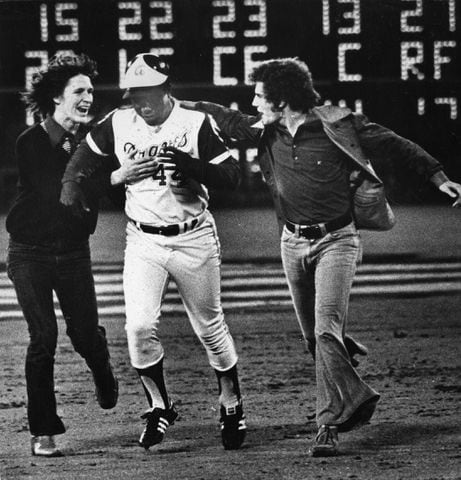

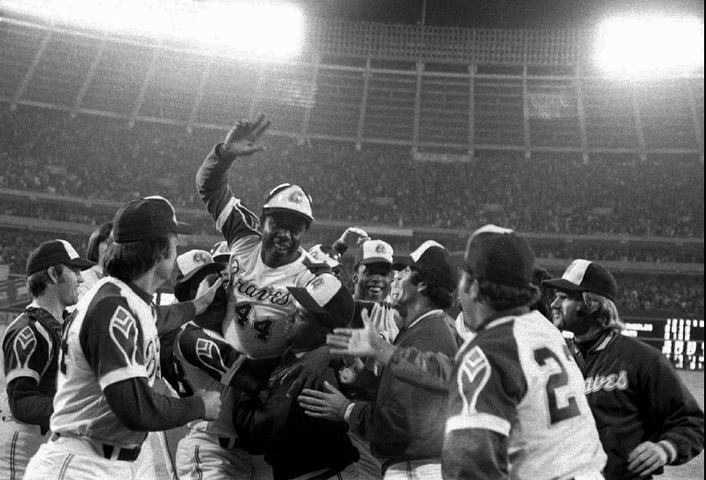

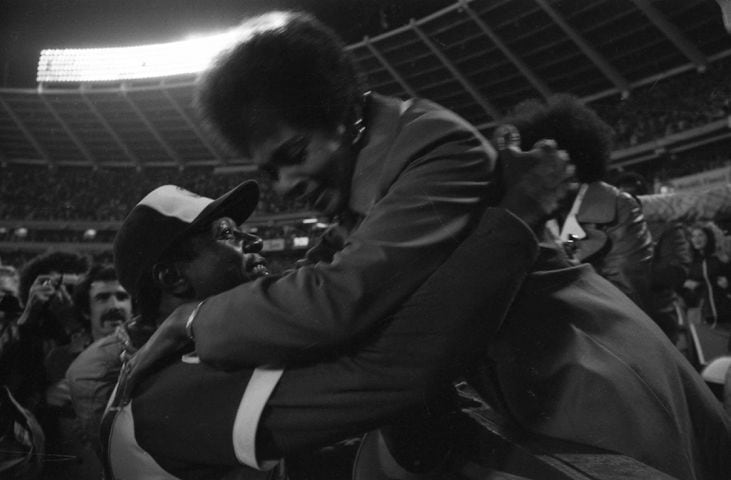

It was almost like I was living a dream. Dad and I hugged and whooped and hollered. Tears streamed down my cheeks. The roar of the crowd was deafening. Then came the fireworks.

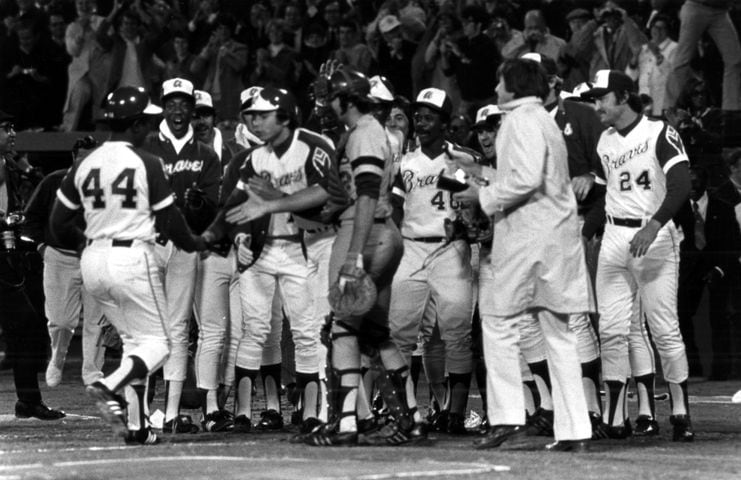

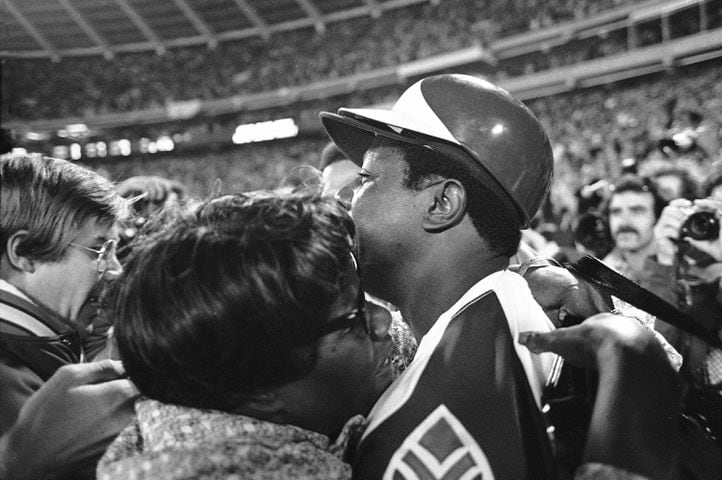

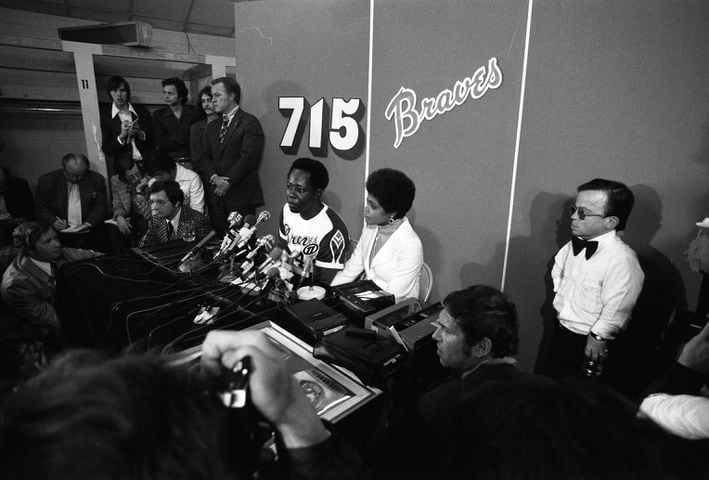

When Aaron touched home plate, his teammates swarmed him and tried to lift him up and carry him. But then Aaron’s father, Herbert, got to him and gave him a hug. That didn’t last long, though. Aaron’s mom, Estella, in a light blue dress, raced up and gave her smiling son the hug of a lifetime, not letting go, her arms wrapped around his neck. She hung on so long that relief pitcher Tom House, who’d caught the record-breaking ball in the bullpen and raced onto the field to give it to Aaron, had to wait a while to do so.

I can still remember how I felt at that moment. My entire body tingled with joy and the feeling wouldn’t go away. Pure elation. It was without a doubt one of the happiest moments of my life. And I looked at my beaming father and said, from the bottom of my heart, “Thanks so much, Dad.”

(Postscript: Two years after my father retired from the newspaper in 1986, after 26 years there, my parents moved from Atlanta to the Chesapeake Bay in northern Virginia. I was out of the country when that happened so when I returned, one of the first things I asked my mom was: “Where’s my stuff?” When she told me it was in boxes downstairs, I immediately went there looking for one thing and one thing only. But the ball Henry Aaron signed on the day he broke Babe Ruth’s record was not there. And it was never to be found.)

About the Author